|

The

setting:

July, 1943…a grass-strip airport somewhere in the US

mid-west…

“Anything for me to do today, Mr. Simmons?”

The man looked up from the workbench where he was

cleaning a well-used carburettor. He squinted against the

bright, late morning sunlight streaming in the open

hangar door behind the boy who had spoken. He didn’t

answer right away, but made a show of picking up the

cleanest of the rags that littered the bench top and

wiping the solvent from his hands.

As he stepped around the end of the bench, limping just

a little on his game leg, a half-dozen thoughts went

through his mind. He considered the boy. About 13 years

old, he was – straight hair, a light brown, but

sun-bleached almost blonde. It was too long, several

weeks beyond needing a haircut. Tommy Harnott was his

name, the only child of the couple who owned the small

farm that lay about three-quarters of a mile up the

dusty gravel road from the airport buildings. He knew

the boy’s dad was off somewhere, caught up in the draft,

or maybe had volunteered to serve in the Army. Only the

boy and his mom were there now.

The place wasn’t being farmed this year, though there

was a big garden behind the house and the small orchard

was bearing fruit. Jim supposed that the farming was

just too much for the woman and the boy to do alone and

there weren’t any men around for hire, able-bodied or

otherwise. They seemed to be getting by none the less.

He supposed that the government must be sending some

money from the absent man’s military pay.

Simmons was the owner and operator of the airport, such

as it was, the only one for nearly twenty-five miles. It

wasn’t much. General aviation was all but dead with the

war on. If it weren’t for the aviation needs of the two

manufacturing plants in the nearby town he’d have lost

the field to the bank months ago. The companies were

doing war work, however, and were expanding as fast as

they could find people to fill the new jobs.

Both companies kept aircraft at the field for the

businessmen to shuttle back and forth to Washington for

contract talks and meetings, or for similar reasons to

the plants of suppliers or of their own industrial

customers. They paid rent for the wood frame hangars

where they kept their aircraft, two for one outfit, one

for the other. They bought some of their gas here, when

he could get it for them, and allowed Simmons to tend to

the maintenance of their aircraft. It was enough.

The boy was a regular at the airport. He’d been hanging

around at the fence line ever since he was old enough to

be out by himself. There weren’t too many other kids

nearby – the farms were far apart here, most much larger

than the Harnott place. Over the last couple of years,

Tommy and Jim Simmons had developed a sort of

friendship; not close or familiar, just an unspoken

mutual understanding. Jim had begun to ask Tommy to help

him from time to time with the occasional chore he

couldn’t handle alone– lifting something awkward,

holding the other end of a long part that needed

attention – that kind of thing. Before long he’d begun

to offer the boy odd jobs, painting, mowing or chopping

weeds, mostly, and paying him a little for doing them.

This summer, Tommy had done most of the mowing out on

the strip and around the hangars and the small office.

“I don’t have much today, Tommy. I do need a lift to get

this crankcase up on the bench, if you can manage that,

though”, he said indicating the shell of a Ranger engine

resting on wood blocks on the floor. It looked forlorn

and empty without its cylinders and other appurtenances.

“OK.” The two bent to the task and in a few seconds the

big aluminium casting rested on the bench, ready to be

cleaned up and prepared for re-assembly. Simmons thanked

the boy for the help, then turned back to the

carburettor. The boy drifted out the open hangar door to

stand in the shade next to the building, looking at the

sky.

Far off to the south the boy's keen eyes picked out a

black dot, low on the horizon. As he watched, it grew

bigger, clearly approaching. Something was odd about it.

The boy was used to the business twins that came and

went from the field, but he seldom saw anything else

these days, at least not low or close. This was

definitely not one of those.

“Mr. Simmons, is a plane coming here today”, he called

over his shoulder.

“No, not that I know of”, replied the man, not looking

up from the intricate parts he was working over.

Over the next couple of minutes the plane slowly

resolved itself into something big enough for some

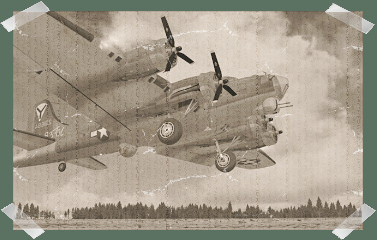

details to become visible. It had a low wing, four

engines and a huge vertical fin. Only one thing looks

like that, he thought. A B-17 – it had to be! Nothing

else he knew of looked remotely like it. But something

wasn’t right. As the plane came closer, Tommy could see

that there was a problem. One wing was low, and the two

engines on the opposite side were not turning. It was

coming here alright, but it was coming on only two

engines.

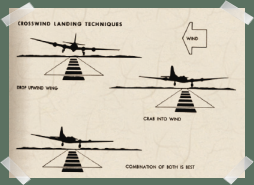

It was

near enough that he could hear the engines now, running

hard as the pilot held the big plane in a maximum effort

slip to counteract the asymmetric thrust. It made its

way toward the field in that peculiar skewed attitude

indicative of hard cross-controlling – ailerons banking

it one way, full opposite rudder preventing the turn.

The big Boeing was crabbing in, losing height as it

came. It was too low and getting lower - too fast for

the strip, but not daring to slow or lower flaps or gear

– yet.

He held his breath watching the arrival unfold. At what

seemed to be the last possible second the landing gear

started down, and the flaps. The gear came all the way

out, barely; the flaps didn’t have time to get even half

way. An instant before the landing gear touched down,

having cleared the low wire fence at the south end of

the strip by a few scant feet, he heard the roar of the

two engines diminish. The nose began to rise a little

and the plane started to straighten itself to align more

closely with the broad grass runway. The low wing on the

port side rose slowly, ponderously, but never got near

to level before the left main gear slammed down onto the

grass, throwing dust and chunks of turf and forcing the

wings level as the other wheel came down equally hard.

Skidding for a heartbeat on the misaligned landing gear,

the big plane then bounded back into the air a foot or

two as the landing gear struts recoiled, before settling

again. It skidded again, but came straight as the pilot

stood on one rudder pedal, then, as soon as it was

tracking straight, on the brakes. It ate up the

remaining strip swiftly, slowing all the while, but

still lumbering on at a good rate. It was rapidly

approaching the end of the strip where the buildings

stood off to the right side. At the end, there was

another wire fence, with a deep drainage ditch and a

dirt road just beyond.

Just as it seemed that a disaster was inevitable, the

bomber turned sharply, hauled around brutally in a

seemingly impossible turn to the right by the right

brake and the left engines - responding to throttles

suddenly pushed open for a few seconds. It skidded

through the turn, throwing up clods of dirt from the

tail wheel and the main gear on the side away from the

buildings as it turned toward them. The turn, almost a

ground loop, sapped most of the remaining momentum from

the big juggernaut and it bumped the final hundred feet

over the rough sod toward the buildings and coasted to a

stop, looking just as if it had been parked there

intentionally. The big Perspex nose was thirty feet from

the front of the maintenance hangar, pointed slightly

skyward.

At some point before that Jim Simmons had come limping

from the hangar as fast as he could manage when he’d

heard the approaching engines. He stood next to the boy,

mouth agape, as the two port-side engines wound down and

clattered to a stop, magneto impulse clutches clicking

out the dying cadence.

|

From the belly just forward of the wing, a squarish

hatch dropped open on a hinge and men began to emerge.

As one after another dropped out of the hatch, Tommy and

Jim Simmons watched the pilot and co-pilot through the

cockpit windows, shutting down systems, then removing

bulky headsets and getting out of their seats. The

co-pilot looked shaken, the pilot unruffled and

confident. The tail gunner came up beside the plane,

having come out at the rear from his own private exit.

The men grouped up on the grass, ignoring the civilians,

chattering about the wild landing. |

The pilot descended from the hatch last, making a total

of ten, four of them officers. He was wearing the silver

oak leaves of a Lieutenant Colonel. A tag on the front

of his flight jacket said, “Elliot”. He gathered the men

around him. The co-pilot, still looking very much like a

man who‘d just gotten a glimpse of the hereafter and

didn’t wish to go there yet, hung back a half step

behind the colonel’s right shoulder, staying out of his

direct view.

“OK, men, let’s get this sorted out. We have a schedule

and we need to get back on it. We’re due to be in

England in three and a half days, and I still intend to

be on time. Let’s take stock and see what we need to do

to make that happen.

Sergeant Weiderczyk, were you able to get off the

message I requested”

“Yes, sir” answered a man, one of several with three

stripes on their sleeves, obviously the radio operator.

“Acknowledgement?”

“No, sir, not that I picked up. I don’t know if they got

it or not. I sent it blind, three times.”

The Colonel turned to the man and the boy who stood a

few feet away. They were staring at him with wide eyes,

hardly blinking, still coming to grips with what was

happening. “Got a phone here, mister” he asked.

Jim replied that there was, in the office. He pointed to

the small building a hundred feet away. The colonel

turned to the radio operator and directed him to get on

the phone and to make contact with their base, letting

them know that they had landed safely, but that

technical assistance might have to be flown in.

The sergeant answered with a curt, “Yes, sir”, and moved

off to do the Colonel’s bidding.

Turning to one of the officers, the aircraft commander

said, “Mister Murphy, you remain entirely responsible

for that Norden bombsight. I want it covered and I want

you next to it, awake, with your sidearm, at all times.

You will have no other duties while we remain here. If

you need a relief for a latrine trip or anything else, I

want another armed officer in your place until you

return. Understood?”

“Yes, sir.” Off he went, re-entering the aircraft.

And so it went. The navigator was detailed to determine

their exact location. Once having done so, he, along

with the radio operator, was to relay it by telephone to

the Army Air Corps authorities, along with any

additional information regarding their situation that

might be available by then. The navigator was soon at

the workbench in the hangar, head-down over a chart, in

deep conversation with Jim Simmons.

Turning to a grizzled looking sergeant who appeared a

little older than most of the rest of the crew the

Colonel said, “Well, MacKinnon, you’re the flight

engineer. What are your thoughts?”

“I’ve been thinking about it, Colonel. They went rough

just seconds after we switched tanks. They got lean,

then quit pretty quickly – just a minute or two, as you

know, sir. Switching the tanks back again didn’t help.

It’s only 3 and 4 that are affected. I’d say we have

contaminated fuel – more likely dirt than water, but

maybe some of both. When they were fuelling us early

this morning we got the last of a truck full on the

starboard side and then another truck filled the rest of

the tanks. I’d bet the starboard side fuel is dirty, and

the strainers are probably blocked solid too. Nothing

else seems to fit the facts.”

“What does it take to put that right, Mac, remembering

we’re out in the boondocks here?”

The sergeant thought for a few seconds – you could

almost hear the gears turning. “It can be done, Colonel,

but we’ll need a pump of some sort that can handle

gasoline safely, some hose or tubing and a filter or a

good fine strainer. A filter would be best. There’s too

much fuel involved for a hand pump. We need to empty the

dirty tanks, either into drums or some other kind of

receptacle. After we clean the strainers, we can pump

some or all of it back in straining or filtering it

clean as we go. I’d like to follow the first draining by

flushing the dirty tanks with more fuel, then draining

again, before we refill ‘em the final time. If we can

come up with a pump, a filter, some plumbing and

containers, we ought to be able to pull it off.”

“OK, Mac, carry on with it. You can use all the enlisted

men except Weiderczyk. Mr. Evans…”, he gestured to the

co-pilot, without turning to face him, “…will oversee

the work on the aircraft. Let him know if there’s

anything you need that you can’t work out on your own,

and in any case, keep him up to date on how things are

going. I’m sure that fella’ from the airport will help

with whatever he has available, particularly when we

tell him he can bill Uncle Sam for whatever we use. Oh,

and as of right now, I don’t want anyone smoking within

a hundred feet of this aircraft. This is a fuelling area

now and will remain so until you’re done and everything

is restored. Clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

|

As the sergeant gathered the rest of the men and began

to work out their plan, the Colonel turned to the

co-pilot, grabbed him by the elbow and steered him away,

none too gently, out of earshot of the others. He turned

then to face the man.

“Captain Evans, you weren’t much help to me on that

approach. I was a little too busy trying to not lose the

ship and these men to enter into a debate of the merits

of bailing out.” |

The captain cast his gaze down to the ground, then

looked up into the Colonel’s piercing brown eyes. “Yes,

sir”, he said, “I apologize for what happened. It’s just

that I’ve never been so scared in my life. I have no

idea how you made it to this field. That ship is not

supposed to be able to fly like that. Colonel, I’ve been

an instructor pilot on the B-17 for the last five

months. I’m supposed to be an expert on what it can and

can’t do. If I hadn’t witnessed what just happened with

my own eyes I would not have believed it was possible. I

thought for sure…no, I knew…I knew we were going to

stall and spin in, or roll inverted or just come down

short. With the gas we’ve got aboard we would have gone

up in a fireball.” He stopped and drew a deep breath.

“I’m sorry I lost it. It won’t happen again, sir.”

“Well, we made it, Captain, and as you’ve just learned,

the B-17 can do some things the Boeing engineers would

have us think it can’t.

For future reference, when I give an order in a crisis,

I expect you to comply, not argue with me. If things are

less tense, I’m willing to entertain your ideas and

opinions, but not with two engines out and every foot of

altitude and knot of airspeed needed to make this

god-forsaken little pea-patch of a field. It wasn’t the

time or place for an ad hoc meeting of the Air Corps

chapter of the West Point debating society.

Now, if you’ve got control of yourself, I want you to

stay on top of the work Mac and his people are doing.

Don’t bird-dog him, but help him knock down any

roadblocks he runs into. Once the fuel operation is

under way to the point where the others can keep it

moving, I’d like you and him to personally look over the

whole undercarriage, wheels, tires, brakes, struts, the

works. We just gave it a hell of a workout and I’ll feel

better knowing Mac has eyeballed it. Make it your idea

when the time is right. He’ll respect that. Report

immediately to me with any problems that appear to

preclude us flying out of here today.”

“Yes, sir. I won’t let you down again, Colonel.”

Turning on his heel, the colonel began to walk toward

the tiny office building. Noticing the boy, who was

staring at him, he stopped short, did a little

double-take and said, “Hello, son. What’s your name?”

“T... To...Tommy, sir,” he stuttered out. “Tommy Harnott.”

“Well, hello, Tommy Harnott. I’m Colonel Elliot – Bill

Elliot. What brings you to this place?”

“I live just up the road, sir. I come here whenever I

can. I like planes and Mr. Simmons lets me hang around

and watch, and sometimes he lets me help him some.”

“Do you know what that plane is”, he asked, nodding his

head back toward the bomber.

“Yes, sir. It’s a B-17, a Flying Fortress. I read about

them, and saw some pictures in a magazine, but I haven’t

ever seen one before. It’s big!”

“Well, big or little, they all want to fly, Tommy.

Sometimes you just have to coax them a little.” He

looked at Tommy again, remembering something from a long

time ago, then added, “Come along son. When he’s done

with my navigator and with MacKinnon, you can introduce

me to your Mr….Simmons is it?”

Just outside the office door the man stopped and looked

around. His sharp eyes took in the airport and the sky,

the hangars and the few disused, single-engine aircraft

tied down in the grass parking area.

Twenty minutes later it was getting crowded in the tiny

airfield office. The sound of a small gasoline engine

could be heard pop-pop-popping through the open door and

window, coming from the general direction of the bomber.

Simmons had been able to provide the pump and the other

hardware that Sergeant MacKinnon had needed and the work

was under way.

The navigator, a Lieutenant Oliver, was on the

telephone. He had already relayed the name and

coordinates of the airfield back to the military

authorities, confirming no damage or injuries, and

explaining the situation. The radio operator stood at

his side, holding a list of hurriedly jotted notes out

for the Lieutenant to read from.

“That’s right! Colonel Elliot says that he still expects

that we’ll make Wright field today, but it may be after

dark. He wants the active runway lighted if we haven’t

arrived by dusk. When we’re close enough to contact

Dayton radio we’ll use the same call sign and IFF codes

that were originally assigned to us this morning.” A

pause. “No, I’m not going to repeat it over the

telephone. Look it up, Mac, or get it on the secure

teletype from our point of departure. We should be on

your list of scheduled arrivals anyway. We’re supposed

to overnight there, get a quick maintenance inspection

and continue in the morning. The Colonel doesn’t, I

repeat, does NOT, want our departure time delayed

because of the late arrival.”

Jim Simmons stood to the side, leaning on a window sill,

listening. The Colonel made a gesture toward the door

with his eyebrows to Simmons, then put a hand on the

boy’s shoulder and moved out into the bright sunlight.

“You got anything for rent here, Mr. Simmons”, the

Colonel asked.

“A car – no Colonel, there’s only my old Ford, but if

you need to go somewhere, I’d be happy to…”

“No, no, an aircraft. Do you have a plane for rent

here?”

Jim Simmons stared back at him, uncomprehending. Why

would this military man want to rent an airplane, here,

now, with all this going on?

“Well, do you”, the officer asked again.

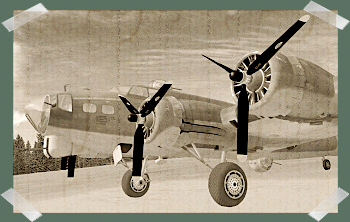

“Ahh, yes, sort of, Colonel. There’s that Curtiss bi-plane

over there. It belongs to old Doc Harvey in town. He

doesn’t fly it much any more – not at all, really. You

just can’t hardly get the gasoline any more. But he’s

authorized me to rent it out for him if there’s ever an

opportunity.”

“I might be interested in a short rental, Mr. Simmons. I

have an old debt to repay. What kind of condition is it

in? I’ve had all the engine failures I care for in one

day. Is it in good shape? Is it reliable?”

“Oh, yes sir. Old doc keeps it up real well. I just did

an annual on it a couple of months ago. It hasn’t been

flown recently, but we run the engine for ten minutes or

so about once a week, just to keep everything dried out

and oiled up. There’s enough gas for that.”

“OK, then, Mr. Simmons, I’d like to rent it for about an

hour. Have you got some flying gear – I’m thinking of

goggles, mainly. “

“Sure, Colonel. I can fix you up. Let me get a pair.”

“Make that two pair!” He looked down at the boy. “You do

want to go, don’t you”, he asked, pulling a wallet from

his pocket to pay Simmons for the rental.

Three and a half hours later, Tommy and Jim Simmons

stood in the doorway of the old hangar, watching as the

B-17 prepared to depart. The men were climbing in. The

tools and equipment used to clean up the fuel and flush

the tanks had been put away and most of the freshly

filtered fuel was back in the big bomber’s gas tanks.

Jim Simmons spoke. “Tommy, I don’t know how he intends

to turn that thing around. I offered to use the tractor

to try to tow it backwards a ways and give him some

room, but he wouldn’t hear of it. He says he can manage

it from where it sits. I don’t see how.”

Tommy, with the old pair of flying goggles still hanging

around his neck by the frayed rubber strap, smiled.

Actually, he hadn’t stopped smiling since he’d climbed

into the front seat of the Curtiss bi-plane, except when

the smile broke into a wide grin every few minutes.

“Watch, Mr. Simmons”, the boy said quietly, “He told me

how he was going to do it.”

Soon all four of the Wright Cyclone radial engines were

running, hammering away at a fast idle, impossibly loud,

warming up the oil. The afternoon sun glinted from the

spinning blades, creating the illusion of phantom

propellers, spinning slowly.

The man above them in the left seat grinned and threw

them a jaunty half-salute, then lowered his eyes to the

business at hand. The last crewman, MacKinnon, had put

away the fire extinguisher he’d had at the ready during

the engine starts. He made his way to the open hatch,

moving carefully along the aircraft centreline from the

nose so as to avoid the deadly arcs of the whirling

propellers. He grabbed the hatch lip and pulled himself

up, then pulled the hatch closed by an attached lanyard.

In a few seconds his head appeared between the two

pilots and he could be seen giving Elliot a thumbs-up

hand signal and talking into the pilot’s ear as the

Colonel held his headset slightly away from his head,

nodding.

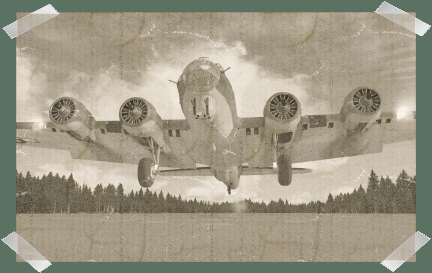

Seconds later, Simmons watched as the left outboard

engine revved up to high power. The opposite wing began

to move – backwards. The bomber was rotating on its left

main wheel, which was under the left inboard engine

nacelle; that wheel was being held by the brake. When

the right wheel had backed about eight feet, the engine

rumbled back to idle, the propeller wind-milling in the

sunshine as it slowed. A few seconds later, the right

outboard engine accelerated and the left wing crept back

eight or nine feet, while the right wheel stayed planted

where it was. The Colonel was backing the big bomber up!

In three or four more such cycles the B-17 had waddled

well back from the front of the hangar, the tail wheel

scribing a saw-tooth pattern in the grass as the tail

swung from side to side. There was clearance enough now

to manage a hard right turn. When Colonel Elliot finally

swung the big airplane, the left wingtip cleared the

side of the building by ten feet or more. His arm was

out the side window waving to them as he straightened

from the turn.

The engines rumbled loudly as the Boeing taxied away

from them toward the south end of the grass field.

There, it would make its turn for the impending takeoff.

The noise of the engines lessened as it rolled away,

opening the distance. Simmons said quietly. “I’ll be

damned. Tommy, that man is a real pilot.”

“Yes,

sir, he sure is. I’m going to be one someday too.”

*

*

*

The

setting:

October, 1924…a farm pasture somewhere in the American

south-east…

Twelve year-old Billy Elliot watched, mesmerized, as the

fabric covered bi-plane glided down toward his father’s

big pasture. Its engine was cutting in and out, running

for a few seconds at a time as a little more gasoline

made it through the iced up carburettor… He could make

out the lettering “US Air Mail” on the big flat side of

the fuselage…

End

Back

to John's Section Home

Works best in!

|