Just Flight®

/ Aeroplane Heaven® DH-98 Mosquito

Flashes and Brass

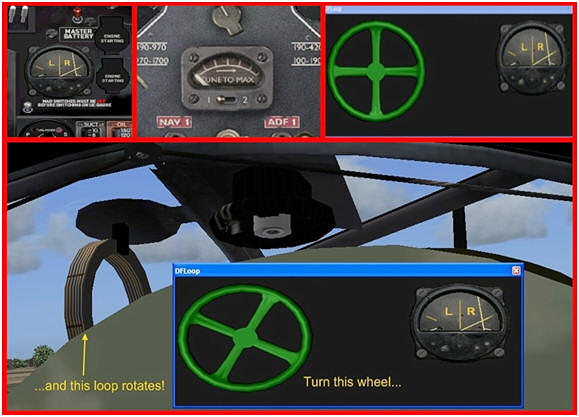

A few items on the features list are unusual and noteworthy. The first is a working ADF loop antenna on certain models, though I had difficulty getting the signal strength gauge to respond properly. The loop antenna pop-up does not have a Simicon, but comes up with the Shft-4 key. There is also a gauge associated with the ADF that I have never seen before, incorporating a pair of needles in a broad V configuration that allow flying directly to a tuned NDB – that works very well. Also there is a working F24 Camera in the PR (Photo Reconnaissance) versions which can be used for taking screenshots.

Radio Navigation, circa 1940

There is also a, “Fully animated, realistic 'blinking' pilot…” who looks very dapper indeed in moustache and polka-dotted cravat – oops, I mean flying scarf. I can tell by looking that he has letters after his name and a house in the country. He usually has his oxygen mask hanging to one side as in the movies. The other crewman, who may either be in his seat or prone in the nose compartment, appears considerably more plebeian and stubbornly leaves his mask on, even on the ground – hangover, perhaps. They say oxygen helps with that.

Wood WorkersCalled the “Wooden Wonder” or “Timber Terror” at times, the Mosquito deserves a better name; those smack of being media creations of the day. Neither of them do it justice, in my opinion. RAF personnel almost universally referred to it simply as “Mossie”, a name that has stuck with it down through the intervening many years. In all my correspondence with JF during the testing, I don’t believe anyone ever referred to it by any other name. I didn’t like the name at first, but have become comfortable with it – if it’s good enough for those who flew it and knew it, it’s good enough for me.

The Mossie was hated and feared by the Third Reich, who felt the effects of it deeply and often from the time of its introduction in mid-war. Though the design pre-dated the war it was slow to come to acceptance and production. The dark days of Dunkirk and the Battle of Britain claimed higher priority and the Mossie was slow to come on the scene. Once arrived, however, it came with a vengeance and proved extraordinarily effective in all sorts of roles.

Herman Goering once decried the fact that the Mosquito was being built in every piano factory in Britain. He was very nearly right. The novel construction materials and techniques played into the hands of a large number of craftsmen in the furniture and carpentry trades. Prior to that, their skills were not able to be very effectively applied toward the war effort. The Mossie provided a project to which their skilled hands could be turned immediately and with great effect.

Built almost entirely of wood with a structure that relied heavily on glue and screws, the Mossie was clearly at odds with the norms of the day for aircraft construction. Though it has been suggested that the design was intended from the beginning to tap less scarce material and labour-skills resources than the more conventional types, I couldn’t find much in the historical record to bear that out. While it is entirely true that it did make use of those things, that does not seem to be the primary driver for the design. It seems to be more the case that the knowledge base of the company lay in that direction and they chose to apply what they knew best. In any case, what De Havilland wrought with their novel methods was destined to become a legendary aircraft that contributed heavily to the war effort, even with its relatively late appearance.

I would go so far as to suggest that the construction methods are not the primary factor in the success. It lies, I believe, more in the concept of a clean shape unencumbered with all the little bits sticking out of it that the designers of so many other types felt necessary. In another country, further east, that concept was not unknown and found expression in various types that were collectively known as “Schnell Bombers”. The concept is that if you’re faster than your enemies in the air, you have little to fear from them. The Mosquito design, after some false starts in the wrong direction on some of the early prototypes, out-schnelled those who originally conceived of the concept. De Havilland made it smooth and clean, eschewed defensive armament entirely, kept the crew to only two, saved weight where they could and hung a pair of the best aircraft power-plant in the world on it.

Mossie is not a lightweight; the empty weight of the various types is in the 13,000 – 14,000 lbs. range. Add fuel and offensive payload and you have quite a heavy aircraft. Maximum weights ranged up to around 25,000 lbs. Neither were a pair of Rolls-Royce Merlins the fuel-economy choice of the day. It takes a lot of fuel to go very far in one of these and that had to be carried too, though at 37,000 feet the fuel burn becomes fairly reasonable. My point is that the wooden construction did not result in an airplane whose good performance came from low weight. It’s a relatively heavy aircraft. That high performance results mainly from powerful engines, a good overall concept, and a good aerodynamic design, well implemented.