|

Chapter 4

"Coping"

How

things change, I reflect as I scan the instruments by

flashlight. Fifteen minutes ago – less, just about five

minutes ago – we were motoring along merrily over

Tennessee with strobes and beacons flashing and the

autopilot dutifully flying our 50,000 lbs of airplane

exactly as we wished it to, talking on the radio to

Memphis Center and finding our way by radio beams.

Well, I thought wryly, we’re still motoring along over

Tennessee, and our gross is still about 50,000 lbs, but

most of the rest of that happy picture has evaporated in

a puff of smoke – or two puffs of smoke. The first took

our radios and autopilot away. The second took most

everything else. Still, there are some bright spots. The

engines are fat, dumb and happy out there on the wings,

just as they were before. Most of our basic flight

instruments are functional and we have a couple of

flashlights to read them by. And Joe just happened to

have a brand new, shiny, hand-held GPS.

He returns to the flight deck after a few long minutes,

and slides into his seat, carefully re-fastening the

belt. He produces two objects; the GPS that may well be

our salvation and - - -? A roll of duct tape? Aha, I

think, realizing what he has in mind.

|

Just the thing for

covering up those disorienting turn coordinators. He

proceeds to do just that. We’re never going to live this

down if they find out about it back in Ocala.

That done, he fires up the GPS and begins to rapidly

push the buttons on the face. What he’s doing is

unfamiliar to me, but he’s clearly spent some time with

it and seems to be confident. |

“Turn right to 020, Boss; we missed the turn at Hinch

Mountain VOR, but we can get back on the airway before

JELLO intersection”, he says without hesitation. I start

the turn, carefully, roll into it, adding a little back

pressure; don’t worry about the airspeed, just stay on

the altitude. I’m rusty, but not too much. I usually do

this kind of thing by twisting the heading knob on the

HSI. I turn through 30 degrees and steady up on 020,

cross-checking HSI and magnetic compass. It looks like

the HSI gyro is vacuum operated. That’s a blessing.

Flying by magnetic compass is possible, but difficult.

I’m still scanning using the flashlight and Joe is

punching keys for all he’s worth, occasionally

consulting our route sheet. He’s entering our waypoints,

I suspect. While he’s busy with that, I’m busy thinking.

This is going to take some thinking through and tonight

will be no time to be behind the airplane. We need to

anticipate everything we can.

Joe gives me another heading instruction a couple of

minutes later and returns to his keyboard. I make the

turn, this time a little to the left. I can see the

back-lighted, four-color display on his new toy, but

it’s too small and far away to read it, much less to

comprehend what he’s doing.

By the time he’s finished, I’ve come to some decisions.

“Joe, I’ve begun to think this through. Let me lay this

out as I see it. If you have suggestions or you think

I’ve overlooked or mis-calculated anything, let me

know.” He nods, watching me intently.

|

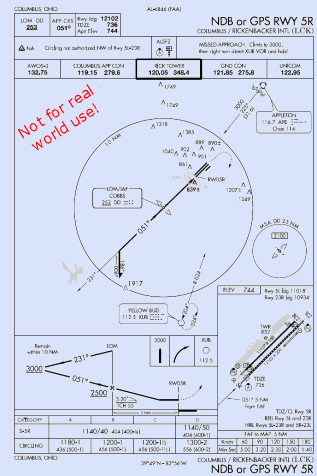

I keep my eye on the instruments as I speak. “I think we

continue to Rickenbacker and should stay at 12,000 all

the way there. I’ve just looked at the approach plates.

5R is the long runway, 12,100 feet plus a 1,000 ft.

overrun pad. There’s a GPS approach for 5R and the IAF

is the outer marker. We’ll fly the last enroute leg

direct to the fix. Once we hit that we can fly a hold

over it and descend in the hold until we’re ready to

shoot the approach. By the time we’ve made one circuit,

ATC will have figured out what we’re up to and will be

getting everyone out of our way. They won’t know we

don’t have lights, but they probably already know we

can’t talk or hear. They must have seen our transponder

go away. I think they’ll be able to follow our primary

radar target better if we stay high. We’ll use the time

between here and there to configure us for landing; I

think it would be best to do that in straight and level

flight anyway.”

“The only navaids on the approach plate are the outer,

middle and inner markers. We won’t have them, but the

GPS should tell us what we need. We won’t have a current

altimeter setting either, but the ceiling is forecast at

800 AGL and the MDA for the approach is almost 400 feet

below that. We should be in the clear well before the

MDA and we can add a couple of hundred feet to

compensate for any altimeter setting error. That will

keep us on the safe side if conditions don’t look like

the forecast.”

|

|

I didn’t know what we’d try next if that didn’t work,

but didn’t say so.

“What was your last fuel hack?” He bent down on his side

and fished out the clipboard, reading it with his

flashlight.

“At KIRCH intersection we had three thousand twenty five

pounds – that was…19 minutes ago.” He sure has gotten

blabby, I think to myself.

“OK, now for the hard part. We need the landing gear and

if possible, the flaps. They’ll have to be pumped down

by hand, and it’s going to take a while, so I want to

start pretty soon. We ought to throttle back some before

we start and get about 20 knots off her, but we need to

remember that the props are as they are. They won’t

adjust without electrical power, so I’m not too sure how

she’ll behave. Ideally I’d like to get the flaps out

first, but I’m not sure we have enough time, so I’m

going to start with the gear and we’ll get whatever we

can manage on the flaps in the time that’s left. With me

so far?” I see his nod out of the corner of my vision.

“Next point is, you understand that little box in your

hand and you know how to operate it – I don’t – and this

isn’t the time for me to learn. Can you fly the plane

and navigate with that thing at the same time while I’m

pumping down the gear and flaps? Remember that you’ll

have to deal with a slow, continuous configuration

change. Do you think you can do that? If you’re not

comfortable with what I’m proposing, say so, and we’ll

think of something else.”

He hesitated for a few seconds, then said, “It’s OK. I

can do it.” I’d never doubted he could, but both of us

needed to hear him say it.

“OK, are you all set up on the GPS?” He nods. “Let’s

slow her down to 145 then. I think you ought to take the

controls, but I’ll stay here until you’re slowed down.

Let’s go a little richer on the mixtures as you reduce

the power. We don’t have any way of gauging that now and

we should err on the rich side.”

A few minutes later we were steady at 145 knots, still

holding 12,000 feet. I hadn’t touched the controls. Joe

had managed the throttles and the trim and the

flashlight and his GPS as if he did this sort of thing

every night. I was ready to jump in if he needed me, but

he didn’t. The props hadn’t been a factor, though we

didn’t have any idea of RPM or manifold pressure any

more. The control scheme must have required electricity

somewhere along the line. I wondered about manifold

pressure and if we were straining the engines by flying

level this slow with the props at a coarse pitch. Can’t

be helped. We get what we get.

“OK, Tiger. I’m going to go back and look over the pump

station, get the valves lined up, then I’ll bring my

flashlight back to you. I want you to have a spare. I

won’t need one to operate the pump. I’ll be back in a

flash.” Another nod, but he doesn’t break his scan.

Twenty more minutes have passed, and I’m back at the

manually operated hydraulic pump station for the second

time. This time I’m in the dark. The pump station is set

in a cavity in the forward cargo hold bulkhead, port

side, just at the deck level. I’d removed the cover

plate and read the instructions on the battered plate on

my first trip here and had already aligned the valves to

pump the landing gear out into the slipstream. All that

had taken quite some time. The pump has two operating

modes, fast and slow. For relatively fast operation, two

pistons, one large and one small, are operated in

parallel by the pump handle to displace oil from the

reservoir into the system. Once operating effort in that

mode becomes too great, and it will, the operator can

slide a little link bar and essentially take the larger

of the two pistons out of the picture. At that point it

will be slow going, but the effort required to operate

the handle will be reduced in proportion. I wonder how

long I’ll last in high speed mode.

Thankfully, the area around the pump cavity is clear of

cargo. The Provider cargo bay is about 31 feet long from

the forward bulkhead to the break of the ramp hinge.

Because of CG parameters, cargo is more or less

concentrated near the center, under the wing, spreading

fore and aft equally. Tonight none of it obstructs the

area around the pump cavity. I make a mental note to

have the almost obliterated yellow “KEEP CLEAR” zone on

the floor repainted soon.

The only reasonably comfortable position for operating

the pump handle is to sit on the floor. My knees

complain a little as I sit myself down and get a two-

handed grip on the handle, which moves laterally,

parallel with the deck, about a foot and a half above

it. It seems that the best position is to sit facing

inboard with my legs parallel to the bulkhead and my

back against the folded ladder of the port side cabin

door. It’s not comfortable, but it lets me move the

handle more or less in the fashion of a rowing machine

and get my back into it. I begin slowly, moving the

handle back and forth in the dark. I’m surprised to find

that it pumps on both strokes. Not sure if I like that

or not; it’s awkward in one direction no matter how I

position myself. Well, it can’t be helped. This isn’t so

bad, I think. I can do this.

About a thousand strokes later, eight hundred of them

after shifting the pump to slow speed mode, I’m

wondering whether I can do this or not. The pump effort

had increased quickly once the gear started moving. I

could hear the change in the slipstream noise as they

began to creep out ever so slowly, pushing the gear

doors open ahead of them. At first I could. Now all I

can hear is my lungs heaving and my heart pumping and my

blood rushing through my tired veins. This is hard work!

I have no idea how far out they are and am wondering how

I’ll know when to stop. I suspect that the pump handle

will become pretty much immoveable once all three gear

legs are up against the stops. I hope so. We don’t have

any little green lights on the panel to tell us.

After a few hundred strokes more, each a little slower

than the last as my strength flags, I feel a steep

increase in the effort required. Within a stroke or two

the handle is solid. Thank God, I think as I sag

sideways against the forward bulkhead for a minute to

catch my breath. I close the stop cock to the landing

gear circuit by feel, preventing the air pressure on the

gear from pushing oil back out of the extended

cylinders.

After that short respite I haul myself, complaining

knees and all, back to an upright position and move

toward the steep steps up to the flight deck. In the

first half-step, I bang my leg painfully against the now

rock solid pump handle protruding from the bulkhead

cavity. Recovering after some salty expletives I limp

the few steps toward the flight deck access way,

supporting myself with a hand on the bulkhead as I go. I

heave myself up, still panting like a dog.

I sit down and belt in, just in case. Joe gives me a

quick look, then returns to his scan. “Gear is down.” I

say as my breathing slows somewhat and I slip my headset

back on. “I’ll need the light when I go back to make the

valve lineup for the flaps.”

“Not much time”, he says.

“How close are we?”

He consults the GPS in his lap. “Thirty-nine miles to

the marker.”

I do the math. A little over 15 minutes. Damn! I was

longer with the gear than I thought. “OK, Joe, I’m going

back right away. I’ll need the flashlight to get the

pump lined up and won’t waste the time to bring it back.

When we’re at 4 miles, shine your light through the

access way and wave it around. I’ll see it and come

back. Be prepared to enter the hold without me, but

don’t descend until I’m back and belted.” Without

waiting for an answer, I pulled the headset off,

unbuckled the belt and squirmed out of the seat,

avoiding the yoke. Once more into the breech…

The flaps proved easier, in terms of effort. I was able

to keep the pump in high speed mode, but couldn’t judge

how much progress I’d made. I can remember a whole

series of actuator cylinders spaced across the length of

each flap, five per side, at least. More cylinders meant

less effort, but more oil. I give up trying to estimate

how far I’d progressed and just keep sawing away with

the pump handle. Soon I see the beam of Joe’s light

waving back and forth through the access way. We’re out

of time. I quickly close the flaps stop cock and this

time, stow the pump handle before making my way back to

the flight deck.

“How does she feel”, I ask after getting settled back

in.

“Nose is down a little, and I’ve had to add power;

they’re down some.” I looked out my side window, craning

my neck to see how much I’d pumped them down but can’t

see a thing. It’s too dark and the angle is all wrong. I

just can’t tell.

Joe banks us into the first turn of the racetrack above

the approach fix. “It’s 231 degrees outbound, left

turns”, he volunteers, trying to look at his watch while

juggling the GPS and flashlight and maintaining his bank

angle. I hadn’t thought of that. The panel clocks were

both dead.

“I’ll call the times for you.” I looked at my watch,

noting the second hand at 5. We needed one minute

intervals, four to a circuit, entering or exiting a turn

alternately at each.

“Let’s talk through our plan before we descend. It’s

going to be busy from here to touchdown.”

“OK”

I consulted the approach plate again. We’ll make the

last outbound leg at 3,000. As soon as we roll out on to

that leg we’re in the approach procedure. I’ll take over

at 7,000 so you’ve got a few minutes to study the

approach plate. Is that enough?”

“Yes”

“OK, I’d like you watching the GPS and giving me updates

once we’re out of the hold. You’ll be our localizer.

Call the procedure turn 5 miles out from the outer

marker. Give me the time hacks for the procedure turn.

Cue me on intercepting the approach course. Once we roll

out of the procedure turn start calling out the distance

to the threshold at one mile intervals. The marker is

exactly 5 miles from the threshold. Final approach

course is 050. We’ll stay level at 3,000 through the

procedure turn, which is to the left. We start down and

cross the fix inbound at 2,500. We’ll use the altimeter

setting we have now and fly all the altitudes as the

procedure shows, but we’ll add 200 ft. to the MDA. That

will make the MDA 1340. - - - Mark, one minute.” He

moves the yoke and the wings roll level.

“If we don’t go missed approach, the field elevation is

744, but we’ll have to remember our altimeters won’t be

very accurate. We’re going to have to eyeball that at

touchdown and we don’t have any landing lights either.

Those runways at Rickenbacker are lit up like the Las

Vegas strip though.”

“I expect they’ll have everyone out of our way, but if

there’s traffic, see and avoid is our responsibility.

Without lights, no one is going to see us until too

late, if they see us at all. If someone’s on 5R, a

side-step to 5L is an option but we’ll have to watch for

traffic. 5L has a displaced threshold and if we move

over, we’ll need to add power and go longer; it looks

like about 2,000 ft. longer on the airport diagram.

They’re close together though. We should get a green

light from the tower while we’re on final, if they can

find one, but if we get a look at either runway and

there’s no interfering traffic, we’ll land, green light

or not.”

“Mark…” another turn begins.

“If we reach 1340 and don’t see anything, we’ll have to

go missed approach, but I surely hope that’s not

necessary. We’re heavy, we can’t retract the gear or

flaps and the propellers are fixed at cruise pitch. I

don’t know how she’ll perform, but it won’t be what

we’re used to. The jets aren’t an option. The starters

and the igniters both need power. I think we’ll be able

to climb but we won’t set any records. The missed

approach procedure is straight ahead on the runway

heading, climb to 3,000, turn right and pick up the 024

radial to Yellow Bud VOR. Hold there. Can you see Yellow

Bud on there?”

He glances down, presses a button. “Yes.”

“We can only guess where the flaps are, so I’m going to

fly the approach at 130 knots. That’s a little over two

miles a minute to get from 2,500 at the outer marker to

744 in five miles. Two and a half minutes for, say 1,750

feet. Sounds like I’ll need about 700 fpm, assuming no

wind. At each mile after the marker, note my altitude

and tell me if I’m high or low. I need 2,150 at 4 miles,

1,800 at 3, 1,450 at 2 and 1,100 at a mile. If I’m on

it, we’ll reach MDA at about a mile and a half. If the

forecast is accurate and our altimeter setting isn’t too

far off, we should break out around two miles. That’s

the closest to a glide slope I can come up with. They

have approach slope lights, so we’ll have some guidance

from them once we break out.”

“I’m going to try to touch down as close to the numbers

as I can. There’s a lot of runway, but I want as much of

it in front of us as I can manage. We’re fast and heavy

and probably don’t have a lot of flaps out. I can’t use

the wheel brakes until 90 knots, but be ready to help me

on them when I do begin braking if I call for it. If I

toast them, they won’t be any help at all. We should

have plenty of stopping distance. What do you think?”

“I’m ready.”

“Mark, one minute.” We roll level again.

“Start us down whenever you’re ready. Use whatever feels

comfortable, we won’t have ATC asking us to expedite

tonight.” He nods and smiles, just a little; he’s

starting to relax. Good! We both need to believe we can

pull this off.

“Keep it fairly shallow. I don’t think we want to get

her sinking too fast.” Another silent nod. “I’ll handle

the mixtures as we descend.”

And so, we’re just about to step onto the down

escalator. I should be scared, I think to myself. Too

busy I guess. If I were just sitting here with nothing

to do this would be a lot worse. We have 9,000 feet of

altitude to get rid of now. If he sets up at 500 fpm

that’s 18 minutes to the beginning of the procedure.

Seems like a long time. Well, genius, it was your idea

to stay high all the way here. Don’t whine about it now.

End – Chapter 4

Click on

logo to download chapter 4 as pdf |