|

Chapter 2

"Cruise"

“Flaps zero.”

“Flaps zero.” Joe’s hand moves and the hydraulic noises

begin, peak, then diminish slowly as the last notch of

the boards comes all the way in. It takes about 12

seconds. Now the noise stops and both the aircraft nose

and the airspeed needle have risen somewhat.

“Shut down the jets”

“Shut down jets”, replies Joe, discarding my superfluous

“the”.

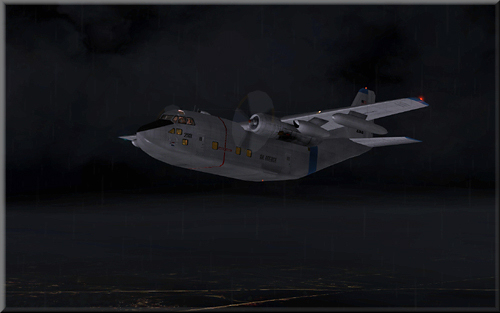

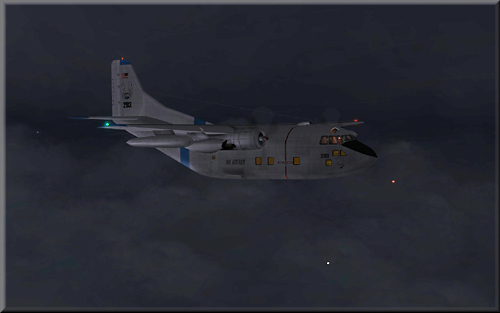

The Provider K-model has a pair of turbojets outboard of

the recips. They’re only used for take-off, but they’re

a blessing when we’re heavy, making short runways seem

longer – and safer. I think of them as a quarter of a

B-52 acting as tugboat for us. Once we’re out of the

harbor, we don’t need the tug any more.

The high pitched whine of the jets that’s just audible

amid the noise of the big radial engines tapers off

quickly as Joe pulls the condition levers back together,

to the flight idle detent. He pauses for 30 seconds to

let them spool down and cool down a bit, then brings the

levers all the way back to the cutoff position. The nose

comes back down some as the jets considerable thrust

vanishes. There isn’t much reduction in sound however,

as the Pratt & Whitneys bellow their climb-out song at

28 inches of manifold pressure. That’s de-rated quite a

bit from their Air Force days. 140 octane gasoline just

isn’t an option any more. If we were to run the boost

any higher on 100LL for any extended time detonation

would likely blow the jugs right off the crankcase.

Still, even at this power setting they’re noisy, despite

the headsets. I love their sound more than almost any

other on Earth. I’ve even been known to slide the left

headphone cup off my ear so I can enjoy it unattenuated,

but not tonight. The doc is close to convincing me

that’s not a good idea any more, and probably never was.

Still, life is good.

“Gainesville approach, Boxwings Freight Flight 201,

climbing through one five hundred for twelve thousand”,

I hear in my head phones. It’s Joe calling on our

departure frequency. Ocala has no tower, so the

procedure is to take off and contact our departure

controller in Gainesville on the designated frequency

once airborne. Gainesville is 40 or so miles north, more

or less along our route of flight tonight. We’ll be in

his area for a while before being handed off to

Jacksonville Center and points north.

“Boxwings 201, Gainesville approach; roger; radar

contact; climb and maintain one two thousand; altimeter

is two niner niner seven.” He doesn’t sound like an

auctioneer tonight. Traffic must be light.

Passing through two thousand feet I begin to pull the

mixtures back a little, starting the leaning process.

That won’t be complete until we’re level at 12,000 and

stabilized at our normal cruise speed of 168 knots. I’m

careful about leaning. We need the power, so can’t leave

them full rich all the way up, but too much of a good

thing is, well, too much of a good thing. Too lean too

soon and the engines will suffer, perhaps even fail if

I’m too ham-handed with this. It’s the thing I pay the

most attention to in the climb, even though there are

about five-hundred or so other things that need some

watching too.

The oil pressure, and the oil, cylinder head and exhaust

gas temps are in the green; I’m watching the latter two

closely as I lean the mixtures another tad. The cowl

flaps are only half-open now. The autopilot is engaged;

we’re tracking an outbound radial from OCF at Ocala,

making 800 fpm at 130 knots. The autopilot is using

almost all the nose-up trim at this weight, speed and

rate of climb, optimal in my book. We’re wallowing along

nose high with this load, but that’s what the wing needs

to support all that cargo back there, and all this fuel

and aluminum, and to still produce enough lift to climb.

The longitudinal CG had ciphered out right in the middle

of the range. It will shift forward slightly during the

night as we burn off fuel though. We were a handful of

pounds under 51,900 at lift off; legal…just. Orville and

Wilbur would be amazed – and proud, I think.

I twist my behind back and forth a little to settle more

comfortably into the designed-to-be-uncomfortable seat

as the tension of takeoff drains away. I continue to

monitor the climb. There isn’t much to do really, except

to bump the mixture levers aft every half-minute or so,

but there’s much that bears watching. Joe’s got the

radios covered; my brain gives that a tiny sliver of

attention, almost sub-conscious. It’s necessary that I

keep my head in the ATC and navigation game, but Joe

will do most of it. He’s changing to the preset

frequency on the Nav 2 radio now and I hear the Morse ID

of the next VOR in the headset for a moment. The engine

instruments are looking good, the flight instruments

show the autopilot flying better than I could and it’s

taking us where we want to go. That’s up, in this case,

and north on the 348 radial. The DME steadily clicks off

the miles, though not too quickly at this speed. The

fuel gauges show about what I expect, but we’ll get a

more precise read of that when we’re at cruise.

We’re flying IFR, of course, so the guy on the ground

staring at the radar scope has the primary

responsibility for keeping us away from other aluminum

objects and them from us. A minute or two ago I noted

that the loom of our lights in the overcast ceased as we

passed through 3,200 feet, indicating we were in the

clear. Now I look out my side windows for just a few

seconds. There’s not much to see, though I can discern

that we are above the cloud deck and there are stars,

but no moon. The overcast below is near solid, nine

tenths at least. I don’t see any other aircraft lights,

and don’t expect to see many tonight except in the

vicinity of Atlanta. None the less it always behooves

one to remember that we’re not entirely alone up here.

Radar and air traffic controllers are good, but not

infallible. I look when I can. At this attitude there’s

not much view ahead and we’re not really going where the

forward windows are pointed anyway, but lower. We’re not

likely to see anyone in that direction unless he’s

descending into us. I direct most of the

look-out-the-windows part of my attention to the side

windows during the climb. If there’s a problem, that’s

where it will appear. I know without looking that Joe is

doing the same on the other side.

Our route tonight will take us through the Atlanta area,

literally right over the busiest airport in the US.

We’ll be level at 12,000 long before that, well out of

the approach traffic. Even at this time of night though,

there will be plenty of other aircraft nearby. Most will

be below us but inevitably nearly every one of them will

have to descend or ascend through our plebian altitude

on their way to or from the patrician flight levels at

18,000 ft. and yonder. It’s still fairly early evening

and KATL has plenty of scheduled air carrier arrivals

and departures until 10:00 or so. It tapers off a lot

after that, but not to zero, and as the airline traffic

dwindles, the air cargo flights increase. It’s a lot

like I-75, but in three dimensions. Both the airspace

and the airwaves are likely to be busy.

The timing is good. We’ll be level at cruise soon enough

for me to enjoy a leisurely cup of coffee, maybe two,

before we begin to get into the Atlanta traffic. That’s

very good. I freely admit to being an unreformed, make

that un-reformable, caffeine addict. It’s not a matter

of staying awake – I managed a couple of hours sleep

this afternoon and won’t be getting drowsy. It’s just

feeding a comfort thing, and will help me be comfortably

alert while transiting Atlanta’s sphere of influence. I

don’t want to be juggling a coffee cup there, so am

thankful for a quiet hour between ToC and Atlanta.

Here we are, coming up on 12,000, nose is coming down,

airspeed’s coming up slowly, slowly, but nicely; now

back a little on the throttles as the speed increases.

Back some with the prop levers, slowing them to a less

fuel-thirsty 1,850 RPM. Keep an eye on the manifold

pressures as the props begin to take a deeper bite of

the cold air. Close the cowl flaps the rest of the way.

Nudge the throttles back some more as we come up on 160,

165, 167….168 knots. Right there! That’s nice. Manifold

pressures look good at 21 inches; now adjust the

mixtures one more time. CHTs and EGTs are good; we’re on

the roof and cruising! Oil pressures remain rock solid,

the oil temps are still high green and will come down

just a bit after throttling back from the hard work of

the climb. The P & Ws are more muted now, but still

loud. The vibration no longer hammers our spines, just

rattles things a bit. Everything looks good, everything

sounds good, everything feels good. Out of the corner of

my eye I see Joe logging a reading from the fuel

totalizer, and ask what he’s showing.

“Fifty-one hundred; five twenty a side.” All right! We

have over five thousand pounds left and each engine is

using 520 pounds an hour. We’re right on the numbers. We

can cruise for almost five hours at this power setting;

more if things begin to look tight and we throttle back.

Life is good.

C-123s don’t normally have a fuel totalizer. We spent

more money than I care to think about having one put in.

The device with its digital readout and controls had to

go on the co-pilot’s side of the panel where there was a

little more unused real estate available. Cargo flights

tend to be loaded heavy, and the trade-off between fuel

and cargo a matter of critical attention for nearly

every flight. Even when we’re not heavy there isn’t a

lot of money to be made ferrying fuel. Sometimes we cut

it pretty thin. Tonight was easy. We had a cargo that

could be divided, with some going along and some left

behind. Other times, that luxury may not be available.

If the payload is a vehicle, for instance, leaving an

eighth of it behind, even if we could figure out how,

isn’t going to make the customer want to seek us out for

future business. That’s not to say we don’t stay legal,

we do – always. But the required fuel reserve for an

alternate airport plus 45 minutes can be pretty tight

when the wind and the weather are against you. We like

to be well on the plus side of that, but it’s not always

possible. The totalizer helps us know exactly where we

are, fuel-wise. My theory is that it will allow us to

make a timely, informed decision to divert if necessary.

A decision based on fact, not on the hair standing up on

the back of my neck while trying to read analog fuel

gauges that might have been plus or minus 10% accurate

when they were designed nearly a half century ago. That,

in my opinion makes the totalizer worth the price, even

if we only have to make that call once.

As I reach behind my seat for the thermos, I reflect on

the mission so far. We had a rough start with the late

arrival of the cargo and the potential overweight

condition. We’ve recovered from those, accepting one,

avoiding the other. All the remaining pre-flight preps

after that were nominal. Start-up was uneventful. The

taxi, takeoff and climb were as planned, just later than

we’d hoped for. It looks like the worst is behind us

now. The late start will not affect things at

Rickenbacker. As long as we’re on the cargo ramp by

0400, no one will have a squawk.

We’ve still got the Atlanta controlled airspace to

transit and the rest of the route to fly, but those

should not present any problem. Our winds tonight are

mainly from the left, forecast to shift slightly behind

us as we get further north. As tailwinds go, this won’t

amount to much. It’s not a headwind at least – no

impediment. The Terminal Forecast for Rickenbacker is

OK. Expected surface winds are light; there’s a broken

ceiling forecast at 800 AGL but with good visibility

below. We’re expecting to shoot an ILS to get in there.

No big deal; we just need to do it right. It looks like

a reasonably good flight, weather-wise.

The coffee is rich and black and still hot enough to

produce steam. I take a first tentative sip, testing the

temperature before committing to a bigger gulp. It’s

just right. As I settle back to enjoy the cup I let my

eyes continue to wander over the panel and the windows.

With the nose nearly level now, there’s a better view

ahead. I can see someone’s beacon far ahead, crossing

left to right. He’s a ways off and will be out of our

path long before we get there. The controller won’t call

him out to us unless he breaks 4 miles, and he won’t. It

looks like he may be heading for Jacksonville; he

appears to be descending.

The air is smooth tonight; no turbulence at all.

Visibility above the overcast is quite good, at least

twenty miles, maybe more. I don’t really mind the night

flying. I’d better not. Flying freight is a

round-the-clock business and a lot, maybe most, happens

at night. I enjoy the pace – and the peace. The sky is

less crowded when it’s dark. You can usually see the

traffic better too because of the A/C lights, except

when they’re lower and against city lights.

The flying public mostly prefers to do their flying as

they live their lives, in the light of day. The airlines

compete for their business by accommodating that

preference. During the day the skies are filled with

jetliners coming and going to and from just everywhere.

There are a few at night, but not many. Those airliners

that are flying are mostly half-empty. The main reason

the companies schedule them is to get the seats where

they need to be for the next day’s business. Even ATC

has a different flavor at night. The controllers are

more relaxed, the pace is slower, and you’re more likely

to hear some banter between the controllers and the

flight crews. The pilots, for the most part are more

relaxed too at night. You’re less likely to be delayed

in the dark, shuttled three area codes in the wrong

direction from your destination to be fitted into a long

line of planes strung out along the approach course. If

you ask for a different altitude or a different approach

or a different runway at night or if you’d like to roll

out on the runway after touchdown and take the last

taxiway, you’re much more likely to have your request

acceded to. It’s not a bad environment.

I debate a second cup as I drain the dregs of the first

one. I guess I’ll wait. There’ll be plenty of time for

more after Atlanta. I stow the cup and scan the panel

again. Everything’s nominal and the engines sound sweet.

“Two zero one, contact Atlanta approach on 132.55; have

a good evening”, I hear in the headphones. Joe

acknowledges and his hand moves to the radio stack. I

muse for a second about co-pilots. I’ll bet they get to

be near ambidextrous if they’re right-handed to begin

with. Everything’s on their left, almost. I try to

remember my co-pilot days, but soon give it up; it’s too

long ago.

Joe clicks to the new frequency and checks us in with

the first of the Atlanta controllers of the evening.

We’ll be handed off to at least two others as we proceed

through their cauldron tonight. I tweak the altimeter on

my side, setting the barometric pressure that was our

token welcome gift from our new controller. Joe does the

same on my right.

I stretch up a little in the seat, looking over the

nose. Far ahead I can see the loom of the lights of the

great Georgia metropolis, just a dull glow at this

distance, diffused by the overlying cloud. Visibility

must be considerably better than the 20 miles I’d

estimated earlier. Atlanta is huge, covering a thirty

mile circle, near enough, but it’s still way off. Closer

to us there are some holes in the overcast and ground

lights are visible through the near ones. Further off,

you don’t see the ground lights or even the holes

because of the angle, kind of a parallax thing. As we

get nearer, more holes will probably appear, filled with

the bright lights of Atlanta and the surrounding area.

It’s time to get prepared for the busy part of the

flight. We’ll have to be watching now. There will be

traffic called to our attention every couple of minutes

all the way through. It’s unlikely we’ll have to change

course or take any other actions, except to make our

planned course change over the VOR, but we’ll make every

effort to eyeball each target called out to us. It’s the

prudent thing to do. Visibility aft of our lateral

centerline is just about non-existent in this plane, but

anything forward of our 9-3 line should be visible

unless it’s under the nose. The auto-pilot is flying,

we’re set up in cruise and everything is stable, so Joe

and I will be able to focus most of our attention out

the windows for the next 20 or 30 minutes.

“Two zero one, traffic at your two o’clock, DC-9,

descending through one six thousand. Report traffic in

sight.” I see Joe looking, bending his head forward a

little to look upward under the top edge of our windows.

Without straightening up, he keys his mike with the

button on the yoke and responds, “Two zero one, traffic

sighted.” Somehow he’s reduced the standard “…have the

traffic…” or “…traffic in sight…” further yet. Well,

it’s started, and we’re still 42 miles from Hartsfield

by the DME. Better stay sharp.

We listen as an audio-induced mental picture of the

terminal area south quadrant slowly unfolds for us. It

sounds a little more frantic than usual. Something’s

different tonight. The weather’s not bad enough to

account for it.

Then, “Atlanta approach Delta 437 is with you, out of

one four thousand, for three point three.”

Atlanta responds with, “Delta 437, roger, altimeter two

niner eight six. Expect vectors for the ILS two seven

left approach.”

There’s a pause, and Delta comes back, “Atlanta, Delta

437, any chance for two seven right or two six left for

us tonight?” He’s trying to avoid having to taxi across

a parallel runway to reach his gate, asking for one of

the runways nearest the cluster of terminals that’s

embedded amongst five parallel runways.

“Negative, Delta 437. Two seven right ILS is down

tonight, and I can’t cross you over to the north side.”

Aha! That’s what’s different tonight. The clouds are low

enough to require ILS approaches and one of them is

toes-up. Forget what I said earlier about a more relaxed

pace at night. Three hours from now it won’t matter, but

this early in the evening Atlanta’s still a very busy

place. With a runway OIA and instrument weather,

everyone will be working hard to keep things flowing.

“Well,” I remark to Joe, “, at least he got his wish. He

won’t have to cross an active runway to get to his gate

tonight.” Joe just nods with a half-smile and returns to

his side window.

End – Chapter 2

Click on

logo to download chapter 2 as pdf |