Introduction

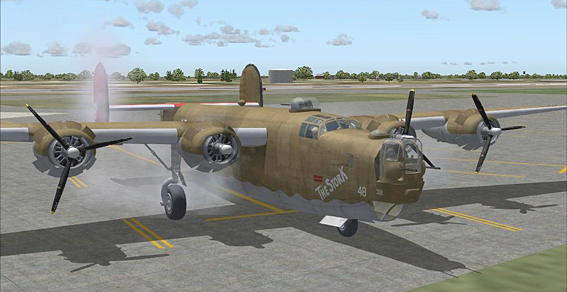

AlphaSim has released another great one. I have a large

soft spot for WWII Warbirds and this one was a major

player in that little fracas. I was pleased and excited

when Mutley suggested I write a review for AlphaSim’s

B-24. I like the plane and I like the publisher. What’s

not to like? This is, by the way, a full-featured

package for both FS9 and FSX.

If you’ve read my work before, you’ll know I’m not a man

of few words. This one’s no exception – a big airplane

deserves a big review. So grab a beer and get yourself

comfortable. We’re going for a ride.

History

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator retains the record to

this day as the most produced US military airplane.

Something in the neighbourhood of 18,500 of all variants

were built, a number made all the more astonishing by

the fact that all were produced in a six-year period,

from 1940-1945. Built in parallel at several locations,

at one point a single factory near Detroit, Michigan was

producing a finished B-24 roughly every 100 minutes,

night and day, seven days a week. I don’t know if the

Nazi government was aware of that; if they were, one

wonders why they did not see the handwriting on the wall

much earlier.

Serving with distinction in the daylight bombing

campaign in Europe alongside its sturdy companion the

B-17, the Liberator also flew in large numbers in

numerous other roles. It was utilized extensively for

maritime patrol, for which it was very well suited.

Dozens of U-Boats met their fate at the hands of

Liberators on long Atlantic patrol flights; many more

were stymied in their hunt for Allied shipping, forced

to hide from the searching patrol bombers, thereby

saving innumerable ships and the men and materials they

contained. The B-24 type was also employed extensively

as tanker and cargo plane and transport and for a number

of other duties. These were not one-off or small time

operations – large numbers were deployed to all of those

less glamorous duties. Winston Churchill’s personal

transport aircraft was a single-tail version of the B-24

which he christened “Commando”.

|

|

In the Pacific theatre too, the B-24 was a workhorse,

put in harness in large numbers following a decision to

standardize on the Liberator as the long-range bomber in

that theatre.

It was used extensively in the PTO by the

US and Allies, shouldering the load as the front-line

long-range bomber until supplanted by the emerging B-29

late in the war.

Here too it served in all those

auxiliary roles, where the vast distances of the Pacific

made its long range invaluable. |

|

B-24 "Cocktail Hour" |

|

Comparisons between the B-24 and the B-17 are inevitable

and rage to this day as to which was “the best”,

particularly where the dwindling company of veterans who

flew in one or the other still gather. Like so many

things, it all depends upon how you measure it. In the

final analysis, comparing all the performance specs, the

Liberator was the equal of the B-17 or better in every

category. It’s most frequently cited drawback doesn’t

appear in the performance tables however. The venerable

Liberator had a glass jaw compared to the B-17, whose

ability to take damage and fly home was legendary. In

that single attribute the B-24 took a back seat.

|

|

|

Over the Target |

By any measure, however, the B-24 was one of the great

planes of the WWII era. Only a few remain today for us

to see. Fewer yet, a mere handful, are still flyable

thanks to the loving care of a fortunate few and the

donations of a multitude who consider the preservation

of such icons important. I had the privilege to see one

of them in person recently and was reminded again how

rare that opportunity is becoming.

AlphaSim is to be congratulated. We who revel in such

things should be mindful that their efforts help to

preserve the memory, the history and the heritage, if

not the actual artefacts of those historic Warbirds. All

too soon, like the endangered species that they are, the

real aircraft will disappear entirely from the skies,

succumbing to old age, corrosion, wear and tear,

accidents and eventually just to avoidance of the risk

of flying something so rare and irreplaceable. In the

meantime, we can enjoy a very credible reminder of one

of the aviation lynchpins of that era. Join me now as we

take a hard look at AlphaSim’s B-24 Liberator, a bird to

remember.

AC Models

|

|

|

B-24 D |

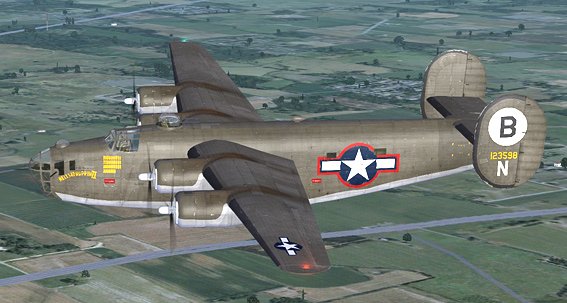

As usual, AlphaSim has put together a credible and

representative package of models. Included are two B-24

D models, those of the glazed and turret-less nose.

There are also two B-24 Js, visually indistinguishable

from the B-24 H (not included). These two near-identical

twins (at least on the exterior) are generally

considered to be the definitive version and together

accounted for about 50% of the total B-24 production

run.

Rounding out the stable is a single example of the B-24

G, sporting the nose turret of the Js, and a nose

section that is so slightly different from the J and H

that only their mother can tell them apart.

|

|

|

B-24 J |

As expected from AlphaSim, the liveries are authentic,

detailed and exceedingly well rendered. The FSX versions

benefit from texture sets created in 2048 X 2048

resolution and are DX10 compatible. They include

“…interior self-shadowing, realistic spec and shine and

custom bump mapping to bring every rivet and surface to

life.” The FS9 versions are also excellent – as good as

anything I’ve seen for that sim. In the face of all

that, simulator performance in both versions was not

adversely affected. Though I didn’t do formal testing of

frame rates, I never saw any ill effects.

UK users might be disappointed that all five of the

models feature US paint jobs, but ownership includes a

paint kit each for FS9 and FSX in .psd (Photoshop)

format. Those must be downloaded separately because they

are very large. This might just be your opportunity to

become an accomplished re-painter.

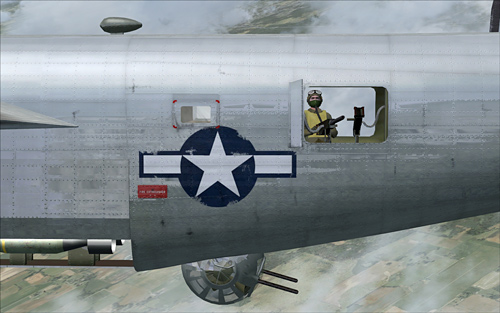

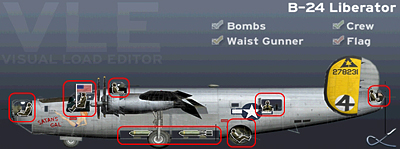

There’s something new to me in this package, a feature

AS calls a Visual Load Editor interface. I’ve seen

various aircraft configuration editors a few times in

the past but they are accessed outside the sim. This one

is a pop-up, able to be used “on the fly” with immediate

results. Shft-6 pops it up and check boxes toggle four

items between visibility and invisibility; bombs in the

bomb bay (you have to open the bomb bay doors to

actually see them, of course), the aircrew, including

gunners, a flag from the cockpit window and most

interestingly, a gunner who appears at an opened waist

door and traverses his .50 calibre gun about. It’s all

about immersion.

|

|

Visual Load Editor |

There’s lots of visual detail, much of it animated. Cowl

flaps have three positions and are individually

controllable from the cockpit from a set of

three-position switches. When the engines are off, the

propellers will feather in response to the prop levers.

All the aircrew are realistically garbed and animated.

Engine starting smoke is quite well done. There are

contrails at altitude, tire smoke at touchdown, and a

faint exhaust plume at lower altitudes – maybe I was

running those P&Ws just a little too rich. Propellers

and spinner hubs appear to rotate slowly and the blades

are a broad blur that changes rate with throttle

settings. These are very good but would benefit from a

full prop disc image too.

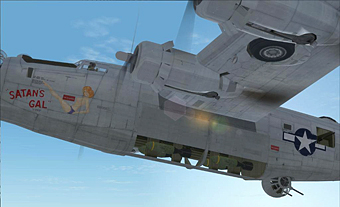

The cockpit side windows have a “blister” that is

visible in the external view. That feature allowed the

pilot and co-pilot to get their eye that little bit

further outboard for better visibility. Landing gear

details are very good. Rolling bomb bay doors of a

unique style on the B-24 cycle realistically and reveal

the bombs if they are turned on in the Visual Load

Editor. The cockpit side-windows slide open on command.

The underside can only be appreciated in flight from the

spot plane view.

The turbochargers, those all-important

devices that allowed the engines to operate at great

height, are set into the underside of the nacelles and

are virtually invisible in ground views.

The ball turret

descends into place in response to the tail-hook key.

The exposed main-gear tires nestle into their

wing-pockets. |

|

| |

Letting it all hang out |

The nose art is very good, ranging from text-only

through mildly profane to bawdy. Some appear on both

sides of the AC. All the exteriors are suitably aged and

weathered with some chipped and scarred paint here and

there indicating a little wear and tear and hangar rash.

There are exhaust stains and oil stains on the wings.

All of these add greatly to the feeling of realism. If

these things leaked oil on the ramp they’d be perfect.

All that is just eye-candy of course, but is a pretty

important part of what we pay for in this hobby of ours.

AlphaSim appears to have spent a lot of time on this and

did a fine job on it. The proof’s in the flying,

however, so let’s go fly it.

Flying

I decided the best way to get up close and familiar with

this thing was to make some long flights. Killing two

birds with one stone, I “bought” the B-24 in my

favourite

cargo-flying game and proceeded to make a trash-hauler

of it. Is that sacrilegious? I hope not. I’ve made

several flights of more than 500 miles each and feel

like I’ve gotten to know the Liberator pretty well in

good weather and bad, in all phases of flight.

No one is ever going to mistake this thing for a

fighter. If you like yanking and banking and inverted

flight, go buy a Spitfire. That’s not what this plane

did. The manual specifically prohibits the following…

-Loop

-360° roll

-Intentional spin

-Inverted flight

-Immelmann

-Vertical bank

I surmise that un-intentional spins and 180 degree rolls

were OK, though I guess maybe the vertical bank rules

out the latter too. I do note that the split-S is not

specifically forbidden, but didn’t try one as I’m too

cheap to risk the resulting cargo damage. ACM manoeuvres

are not what the Liberator was built for. You might be

able to make it roll but the guys flying them in 1944

were getting white knuckles doing their very best to

prevent that. What it did best was haul a heavy load a

long way while carrying enough defensive armament to

keep the wolves away from the door – mostly - when in

the company of a sufficient number of its brothers.

|

|

|

Showing off external self shadowing (FSX Only) |

|

When you mount the beast, you’ll see a box asking you to

make a choice about controls. This takes a little

explaining.

There are 12 levers on the quadrant and that

does not include prop levers, whose function is done by

switches in this AC. There are throttle and mixture for

each engine of course, but the extra four are for the

turbochargers. If you want realistic control they have

to be set separately from the throttles, BUT, if you

decide to do that you cannot use an external throttle

control.

If you decide you can live without the realism

of the separate supercharger controls, you can signify

that and continue to use your external throttle. The

supercharger levers will follow the throttles and MSFS

will do its magic in the background – as long as you pay

attention to the mixtures. |

|

Throttle Pop-up |

Checking weight and balance yields a surprise. We’re

3,300 lbs overweight. The default load-out is ALL the

fuel, ALL the bomb load and ALL the crew (at 220 lbs

each, lugging all that sheepskin and survival gear). If

you want a lesson in aborted take-offs or flight in

ground effect while exploring the back side of the power

curve, leave the loading as it is. Just like most AC of

the period, you can’t fill everything and fly, at least

not very well. Life is full of compromises. In WWII, how

much bomb load you carried was determined by how far you

were going and how much fuel you needed to get there and

back. What remained of the payload capacity when the

required fuel was aboard fixed the bomb load.

Engine start is satisfyingly realistic, but not so

complicated as to be a pain. Battery switch on, set the

brakes, line up the fuel valves, fuel boost pumps on,

set the levers, hit the primer, turn on the mag, press

the starter. When the RPMs and oil pressure stabilizes,

turn on the generator. Repeat for each engine – it’s as

easy as 3, 4, 2, 1.

|

|

|

Starting #3 |

|

|

The primary engine gauges are great. Manifold pressure,

RPMs and oil pressure gauges are dual indicating types

on a common scale, one for each pair of engines with the

engine number legible (really, they’re legible) on each

needle. There are dual face gauges of a different type

for oil temperatures and cylinder head temps and

carburettor inlet temps.

They look realistic, suggesting

the instrument types of the period. For the most part

they’re easily read and in any case have mouse-over

labels that pop up with the readings. They are entirely

satisfactory, though in a few cases near the right edge

of the screen the tabs are partly out of view. Lacking

are exhaust temperature gauges, which would make precise

leaning of the engines easier. CHTs are OK, but are much

slower to respond.

|

|

Collage of Gauges |

Fuel gauges are on a pop-up along with the generator

switches, voltmeters and an ammeter.

The gauges are –

I’m not kidding about this – a pair of level glasses.

There’s a small valve below each to line them up to read

the second set of tanks. Now, for real, the system is

more complex than it seems. It included remote

transmitters and such behind the scenes in the real AC.

It’s more than just a simple gauge glass, but what you

see are two sight glasses. That’s the style of the

readout - more of that immersion we love.

Controls and instruments are well laid out. There’s a

sim-icon in the 2D cockpit to take you to the co-pilot’s

side because everything can’t be seen from the left

seat; another button takes you back. The co-pilot has no

flight instruments except a mag compass. If you’re going

to drive, you have to do it from the

left side.

There

are icons for the radio stack (a short stack – more

later), the throttle quadrant, which has a lot of other

things too, and the fuel and electrical panel.

There are

also sim-icons for the GPS, the map, the kneeboard and a

toggle for the yoke. One nice touch is a panel switch

(not a sim-icon) to centre up the outside view if you’ve

“raised the seat” on approach. You don’t have to bat the

spacebar to get back to the correct point of view as you

cross the threshold – just click the switch. |

|

|

Fuel & Electrical and Radio Pop-ups |

You’ll like the VC. It’s clear and easy to use. What I

like best is that if you centre it up you have a good

view out the window AND can see all six of the primary

flight instruments AND the OBI without having to scan

around. It’s made with approaches in mind, even an ILS

if you need to. Most VCs are not laid out so well. OK, I

have to admit it’s the magnetic compass that’s visible

in that view, not the DG, but it’s still a pretty good

set of what you need on approach, all within view

without panning.

|

|

|

Virtual Cockpit – Zoomed Out |

The DG is up on the centre of the panel, above the rest

and realistically blocks the view to the right front.

The heading bug is a pair of parallel lines that frame

the indicator needle when you’re tracking it. The DG

takes a little getting used to. It’s like a clock. The

hand moves, the scale does not. If you’re flying west,

the needle points to your left. The rotating card and

lubber’s line we’re accustomed to is nowhere to be seen

– except in the magnetic compass.

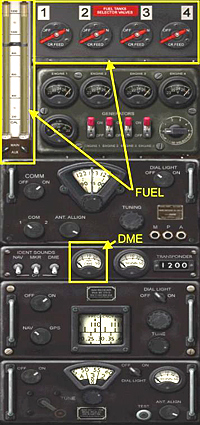

The radio stack is convincingly “period”, all

black-painted, stamped metal faces with white celluloid

dial cards and a hint of pre-historic, or at least

pre-silicon electronics. There is one COM radio but it

has a switch that lets you use it as two. There is one

NAV radio and it doesn’t have that switch - one is all

you get. There is a DME readout, but it’s a little tiny

ovaloid analogue gauge with a logarithmic scale and damned

few markings. There’s an ADF that’s pretty conventional

in operation but with primitive controls (including a

hand-crank) and readouts. There’s a transponder window

for setting the squawk, but none of the other bells and

whistles that transponders usually have. There’s a

switch for hearing the NAV Morse ID, one for the marker

beacons (and a corresponding light on the panel – just

one) and one for the DME ID. Can you fly IFR with that

stack – yup, if you’re good. Fortunately things don’t

happen all that fast at 150 mph.

OK, with engines running and all the gauges in the

green, we’re ready to taxi. Release the brakes and push

the throttle to the recommended 17 inches of manifold

pressure. I haven’t mentioned the sound yet. It’s good.

It’s really, really good. I’ve recently invested in one

of those devices that clamps to your chair and does to

your butt what a sub-woofer does to your ears, but isn’t

so annoying to the pets and other innocent bystanders.

In about two seconds you’re utterly convinced that your

chair has been placed between two pair of R-1830s…and

the best is yet to come. AlphaSim also provides a pair

of alternative sound files that have an increased level

of turbocharger noise – even better, though my

"ButtKicker" clamp-on doesn’t respond to that kind of

noise, just the low tones and thumps and bumps. Of the

dozen or so AC of all types I’ve tried it with so far,

the physical effects rendered to the chair from the B-24

is the best yet. More immersion.

|

|

|

Cowl flap positions |

For me, the test of software that models a big airplane

is whether it feels big and heavy. Some don’t. If I

wanted to fly a Cessna, I’d fly a Cessna. Taxiing this

one feels right. The subtle inertia things are all

working like they should – it coasts a little when you

pull the throttles back, but not too much. It doesn’t do

that wobble-and-waddle thing that some of the lighter AC

do when they first begin to roll. It lags when you

accelerate – the engine sounds come first, but the

thrust takes a second or two to come on. The eye-point

is right and the swing of the turns and such are

convincing.

At the threshold, cowl flaps go to only half-open, flaps

three notches out – 20° – hold the brakes and bring the

throttles all the way up slowly. When you begin to

flinch at the thought of being pelted with broken

rivet-heads from the airframe, release the brakes.

You’ll have about 50 inches of manifold pressure and

she’ll begin to roll down the runway, ever so slowly.

Did I mention you need a long runway? It does track

fairly well; even with reality sliders at full, the

torque and p-factor effects are easily manageable with

just a touch of rudder. At 100 mph, set aside the

magazine article you may have been reading, make sure

the co-pilot hasn’t dozed off and begin to add back

pressure to take some of the weight off the nose wheel.

Some time later, when she’s darned good and ready and

not a moment sooner, the nose will begin to come up.

Care is needed to avoid dragging the tail-skid, which is

bad form and doesn’t help at all with getting her off,

but does keep the crew awake. Eventually, at around 125

mph she will begin to fly, unless of course you’ve

already run out of runway.

There’s an interesting line in the take-off check list…

“Depress wheel brakes once airborne to stop wheels.”

|

|

The Liberator main gear fold outward

when retracting (pretty neat to watch).

If the main wheels are still rolling

about 100 mph and you flip the gear

switch, bad things happen.

I won’t embarrass you by asking if you

remember your high-school physics but

the phenomenon of gyroscopic precession

comes into play and a nose-down force

results.

In heavily loaded real-world B-24s this

was a serious problem if that simple

check list step was overlooked. |

|

Outward-Folding Main Gear |

Five seconds after lift-off and clawing for

the first few hundred feet of terrain clearance is a bad

time for a nose-down input from any source. I tried to

detect that effect in FS and couldn’t. I don’t think the sim engine is capable of modelling it. From my reading

elsewhere, it was not subtle. None the less, our friends

at AlphaSim kept that step in the check list to keep

things real. My respects, gentlemen!

After that hair-raising take-off performance, once

cleaned up, the AC climbs surprisingly well using the

recommended speeds and settings, 170 mph, 46 in. Hg and

2,600 RPM. Leaning is critical as you climb but the

turbochargers carry the day and power remains strong

most of the way up to the service ceiling of 28,000

feet. Once there, 33 inches and 2,200 RPM yields a

miserly 2,000 pph or so, which will take you a fair long

ways in an AC that carries over 2,800 gallons of fuel.

Fuel burn during the climb is another matter, of course

and is anything but miserly. I learned to figure 2,000

lbs to climb, 2,000 per hour to cruise and a 2,000 lb

reserve. It’s easy to remember, but be happy Uncle Sam

is buying the gas.

Interestingly, the B-24 has cruise flaps, a setting that

deployed them to 8°. They were prescribed for flight at

or above 25,000 feet and airspeeds up to 170 mph

indicated, though were especially important below155

mph. Everything, by the way, on the B-24 is, or should

be, in mph, not in knots. The airspeed indicator is in

mph and most of the technical references in the 27 page

PDF manual (though not all) are too. The cruise flaps

lower the nose slightly and make up the lift lost due to

the lower angle of attack. The effect is to create the

same amount of lift while slightly reducing overall

drag. They work.

Cruise speeds of around 150 mph indicated result from

the recommended settings. At 28,000 feet, that’s a GS of

around 210 and isn’t so bad. You can push up the MP and

go a little faster but the fuel burn is shocking.

For the purists who choose the realistic supercharger

controls, AS includes an Excel spreadsheet that allows

balancing the throttle and supercharger settings to

achieve the desired engine power at a given altitude – a

nice touch.

|

The included autopilot looks nice (rustic, but nice) but

isn’t really capable of much except tracking a heading

and holding an altitude.

It does those very well. The

OBI needle(s) respond to the radio but the AP doesn’t

seem to be capable of tracking anything except in

heading mode.

It’s not as bad as it may sound and is

probably relatively realistic.

Descents are a protracted affair and need to be planned

fairly well. A rate up to 1,000 fpm is comfortable and

airspeed is easily controlled. Get it a little too much

nose down and things can begin to diverge on you. My

hard-earned advice is, manage it, don’t chase it. |

|

|

Autopilot |

Approaches are good once you come to grips with the fact

that the airspeed indicator is in mph, not in knots and

your speed isn’t really as high as the numbers on the

meter might suggest. You should keep your brain in the

loop at all times. The Lib is well behaved in the

approach; gear creates a little drag but not much pitch

change. Flaps do affect pitch in the expected fashion,

but not severely. The AC reacts to inputs in a staid

manner, just as if it really weighs 50,000 lbs or more.

Did you remember to retract the ball turret? If you

think dragging the tail skid is dramatic…

110 mph is a good approach speed and slowing to 100 over

the threshold is advisable. A little flare is needed to

ease the descent rate, but remember that tail skid – too

much nose up is not going to make you popular with the

crew chief later. If you’re landing back where you took

off and you fly the approach by the numbers, you’re not

going to have to worry about runway length. If you had

enough pavement to get it off you’ll have a lot more

than you need to get it stopped, even if you’re still

heavy.

Conclusion

AlphaSim did a great job on this one, though it’s no

more than I’ve come to expect from them. They are very

good at choosing aircraft types that capture the

imagination and then making them seem real. That, after

all, is the ultimate compliment for a simulator add-on

like this – to be able to say it seems real. This one

surely does.

I was able to manage realistic medium-range cargo

mission profiles at high gross weights in IMC conditions

and could have done much longer ones. Navigation with

the limited and primitive radio gear does require a

little different technique and a little more work but is

not problematic. The GPS is available, but not

necessary. With some practice it was not a difficult AC

to fly at all, though takes a little familiarization if

you’ve been hanging out in glass cockpits with ITT

gauges.

This one is not just eye candy that leaves you short on

the things that make an AC rewarding to spend time with

in FS. It has everything you need to fly it

realistically, either in today’s ATC environment or in

re-creating the real-world missions flown by the heroes

of the 1940s. Fly it heavy, high and far and experience

a little of what they did. It’s an eye-opener. Set the

weather for a 5,000 ft, 9/10 overcast, launch from RAF

Shipdham and see if you can find Berlin without using

the NAV or ADF or the GPS (Navigator to Pilot: Sir,

…what’s a GPS?)

The Liberator goes for around $46 USD or a bit under £24 GBP. It’s

well worth it.

John Allard |